New Year’s resolution No. 12: Make a good recipe for yoghurt ravioli

January 17, 2006

Ever since I’ve been back in the city, all I do is act like I’m not busy at all and that these short, dark days are endlessly long. It feels like I’ve got all the time in the world, which I’m guessing is a sign of mental health. Please don’t let the Languedoc wear off.

In between all the other ‘very urban, very important’ things that absolutely must get done this week, all involving lots of writing and revising and asking for huge amounts of money from those that keep our culture out of harm’s way, I somehow got the notion that now is the perfect time to develop a recipe for yoghurt ravioli. ‘Make a recipe for yoghurt ravioli’ is literally at the top of my to-do list. Imagine having my brain for only a day.

It’s the journey, not the destination, and true to form, I didn’t ask the source of my inspiration how they made their yoghurt ravioli, preferring instead to embark on a lengthy process of experimentation. Actually, all the experimenting has yielded some pretty important material information and several methods for preparation, so I’m glad I decided to not confer with those more knowledgeable and just figure things out for myself. When I think I’m done, I’ll feel more like I’m sharing and give them a buzz. Fortunately the recipe so far seems to involve a fair amount of waiting for things to drip.

Yoghurt Ravioli (recipe in development)

These are not ‘ravioli’ that you are going to cook. This is essentially a recipe for little disks of Dutch ‘hangop’, or drained yoghurt, sandwiching a filling. The fattier the yoghurt, the easier it will be to make this recipe work.

linen or tightly woven cheesecloth ~50×50cm

a big ‘ol rubber band

a large deep bowl

Fatty Turkish yoghurt (10% fat! If you can’t get this, add creme fraiche to 5% fat yoghurt - fat is good)

fleur de sel or finely ground sea salt

Soak the linen in water and wring it out. Give the cloth a good ’snap’ to shake out the big wrinkles. Place the cloth over a large bowl and secure it with a rubber band, spanning the cloth tight like a drum head and pulling down on the opposite corners a few times to achieve extra tautness.

In a wide mouthed jar, add the salt to the yoghurt and give it a good shaking. Pour the yoghurt mixture in blobs onto the linen cloth. Make rows or a symmetrical pattern to help ease the removal of the ravioli. You’ll see why you need to do this later, trust me.

Let the yoghurt drip for at least 6 hours. No need to refridgerate unless you have food phobias.

To remove the ravioli: Try to keep the linen cloth flat, avoiding as much as possible letting it bend because this could cause the ravioli to crack. Slip the rubber band off the jar and carefully lift the cloth onto a flat surface.

To fill and remove the ravioli: Place a filling on a ravioli bottom, and then, lifting the cloth, fold it over to place a ‘top’ onto each ravioli, gently letting the ‘top’ stick to the bottom. Very carefully peel back the linen, as you would remove the back liner from a sticker, and let gravity help you in this endeavour whenever possible. Do this to all of the ravioli.

Some of the many possible fillings may include:

roasted (pickled) red peppers out of a jar

saag (spiced creamed spinach)

a hunk of smoked herring or mackerel filet

tapanade

think of yer own dang filling

thawed fresh frozen peas and crumbled sheep cheese in brine

Serve up some soup that marries well with dairy, like spicy pumpkin, or borscht. It’s too wintry to fuss with contrast. Contrasts are summer’s business. Over the awaiting soup bowl, peel off the ravioli from the linen tea towel, letting it slip gently into the soup. No plopping. Nice and easy.

debra at 22:40 | Comments (2) | post to del.icio.us

Vegetation and art

January 13, 2006

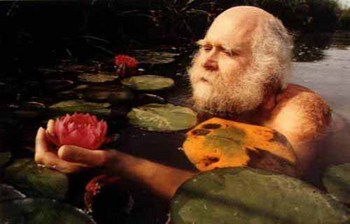

(image: herman’s meadow, copyright herman de vries)

This is an image of a meadow surrounded by farmland. Left to it’s own devices, the meadow has developed it’s own ecology, separate from the agricultural land surrounding it. The meadow is also an artwork by herman de vries, artist/botanist/publisher, who spells his name with small letters on purpose. As a land artist using the natural world as his medium, edible and medicinal plants feature frequently in his oeuvre. In an art in the public space work in the Netherlands, he planted a suburban neighbourhood with more than thirty-six species of heirloom pear and apple trees.

de vries’ work aims to create a heightened awareness with our ‘life-space’. A botanist trained in applied biology, his innovative publications frame natural products such as rose petals, thistledown, barks, mosses and roots, provoke a response far from scientific detachment. Think of an encyclopedaeic herbaria, dripping with passion and scribbles in Sanskrit, and you will have a good idea of his ‘Natural Relations, eine Skizze’. The herbarium includes more than two thousand plants and herbs, collected and logged, but the selection comes from de vries’ own memory! How’s about them apples!

The text below is de vries’ 10 theses on vegetation and art that I plucked from a book titled, ‘Transplant, Living vegetation in contemporary art’, edited by Barbara Nemitz.

vegetation and art

10 theses

* living things should be treated with repsect for their own message.

* nature is our primary reality. the experience of nature is a universal human value. vegetation is the basis of our existence.

*in art, nature becomes revolution.

* bonsai, constricted and malformed trees or plants are not art. they are perversion.

* in dealing wtih vegetation of plants in art, the artist needs in-depth knowledge about what he is working with.

* to bring plants and art together is a challenge for art.

* art in nature is totally superfluous. art can add nothing of significance to nature. the statements of nature are perfect.

* the restoration of natural relationships can be an artistic act.

* in view of what we imagine nature would do without human intervention, a park is, generally speaking, culturally impoverished nature.

* the ideals of the zen garden - asymmetry, simplicity, spontaneity, the absence of formalism - are nowhere as clearly accessible to visual experience as in naturally flourishing vegetation.

what wonderful things are “abandoned lots”, terrain vague, where mugwort, blackberries, thistles and wasteland take over.

- herman de vries

(used without permission from the publication; Transplant, Living Vegetation in Contemporary Art, edited by Barbara Nemitz / Hatje Cantz Publishers, ISBN 3-89322-971-X) www.hatjecantz.de

(image of herman de vries, copyright herman de vries)

- Michael Fehr on herman de vries’ meadow

- about herman de vries, Visual Research Centre, University of Dundee

- herman de vries, Sculpture Projects in Munster DE, 1997

- Dutch Foundation for Art in the Public Space, herman de vries, North of Overijssel Water Estate

- Dutch Foundation for Art in the Public Space, herman de vries, the Garden Village Collections

- October, February, June, a 1977 work by herman de vries translated into hypertext

- Individual Editions, artist editions of plant-related work

- Transplant, Living Vegetation in Contemporary Art, edited by Barbara Nemitz

debra at 21:56 | Comments (3) | post to del.icio.us

Weedy plot, commuting, cover crops and humble pie

January 11, 2006

People who know me well would never say that I’m a practical woman. Now, all the more so. I’ve left my winter quarters in Occitania to return to the Polar Circle, where paid work is calling. Screaming, really. In gardening there’s a time and a place for everything, and ever since I’ve had this garden, my commuting life-style has forced me to ignore this simple rule of nature and do things at the wrong times. Sunday, I finished turning the earth by hand on both allotments. One hundred and sixty square metres. That’s seven in dog years, carry the three, and if you’re not impressed, I don’t care. I’m totally impressed with myself.

It’s a funny thing in our allotments, all the women are organic gardners, and all the men are not. I don’t know if that corresponds with some kind of hippy statistic, but that’s the way it is. And there’s a great deal of social control, you can’t just let your garden go to pot, just because it’s yours. I decided for this reason to experiment with growing cover crops, a crop just meant to keep out the bad weeds and condition the soil in the process. It’s absolutely unconventional around here, and for this reason, I’d been preparing my neighbour, spending time talking to him about my experiment, to let him get used to the idea.

I’m talking about my very sweet neighbour AlGouche. The one who built the retaining wall/serre without my even asking for it, the one who waters my garden when I’m up north, the one who makes me sit down and eat a lunch of barbequed chicken and wine that he’s prepared on his little fire when he thinks I’m working too hard (il faut manger), the one that feeds his garden little red and blue pills. I’ve been telling him for a week now, that before I leave Occitania, I’m going to plant a crop full of weeds, on purpose. Buckwheat, alfalfa, mustard, soybeans and adzuki beans, not for eating, but to improve the soil composition, keep down the real weeds, and give me an excuse to use that turquoise blue rototiller that we just bought. (I read that each time you use a rototiller you have to add 6% organic material to the soil so as not ruin it’s texture.)

Plants not for eating? Al Gouche shakes his head, and tells me in a Moroccan-Occitanian dialect that I’m meshuggah.

The last days, I turned one hundred and sixty square metres of earth with a spitfork. The men of the allotments, bored out of their skulls with winter-lack-of-work, gather daily at AlGouche’s shed for gossip and beer. That’s ‘man’ for tea and sympathy, I guess. But on Monday, my last day in the garden, before departing for Amsterdam, I was completely shocked to overhear AlGouche defending me to the other men. ‘She’s not planting real weeds, just some plants that will improve the soil.’ My heart lept.

And now I’m praying, and looking at the Occitanian weather report from Amsterdam, that the seeds that I have ever-so-crazily planted in January, and that really is meshuggah, will somehow sprout and thrive, beat the weed-race on my little plot of land, between now and March.

Subsistance farming really is a nerve wracking affair, part-time susbsistance farming, even more so. I keep telling myself that if this experiment doesn’t work, nothing will be wasted but a few handfulls of seeds, one day of planting and a huge amount of pride. Which is expensive. Upon leaving the garden Monday evening, I say a little prayer for all the microbes and the earthworms, hoping they enjoy the oysters shells I crushed into the soil, hoping they enjoy the leaves and rotted corn husks, hoping the little legume seeds will grow, and win the growing race for the most light, water and nutrients. Please little legumes, winter cover crops, fix the nitrates in my soil, and produce as much biomass as you possibly can. I’m counting on you.

debra at 0:34 | Comments (2) | post to del.icio.us