Episode 1, emergency food distribution and the role of the cameras

March 19, 2006

- This entry refers to food distribution as discussed in yesterday’s entry about the World Food Programme’s computer game, Food Force.

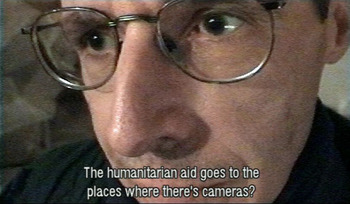

video still from Episode 1, © Renzo Martens

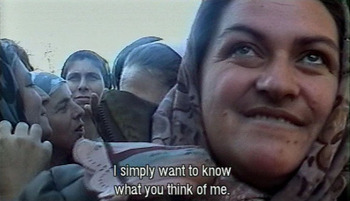

In January 2004, Dutch artist Renzo Martens produced his forty-four minute art film, Episode 1, a documentation of an extensive art performance. Martens travelled to the hottest hot spot war that he could find at the time of making the film (Chechnya, 2002), and in this ’setting’ he pointed the camera, not at the war’s victims and/or perpetrators like most (news) cameras do, but back upon himself. In Episode 1, Martens asks his Chechen and Russian Federation subjects, ‘What do you think about me?’

Enough about you, let’s talk about what you think about me.

Martens subjects are the normal cast of characters in every war; heavily armed soldiers on border patrol, civilians lining up for food, civilians trying to get on with it, civilians suffering before their destroyed homes and lives, refugees, but also all manner of NGO employees with their food programmes and journalists with their stories. Within minutes we understand that this is not simply a film about war, but a film about the role of the camera in war, about ethics, the dehumanising effect of pointing the camera and about what is so humanising about turning the camera back around at one’s self.

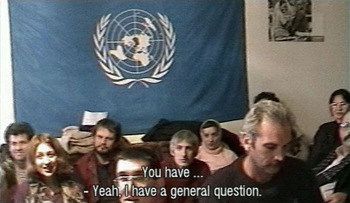

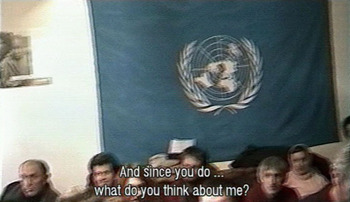

video stills from Episode 1, © Renzo Martens

In the tense environment of a Chechen UN press conference, in territories under fire, the conference moderator asks a group of journalists, NGO employees and UN workers, ‘Does anyone have any questions?’ Martens pipes up, ‘Yes, I have a question!’ ‘What do you think about me?’ Peals of laughter, no one can believe their ears. Ultimatey Martens’ question is ignored and the journalists and NGO employees disband to their SUV convoys, rushing off to yet another ‘opening’ of a milk powder storage facility. Martens interviews the director of the operation, and together they quickly establish the fact that where there are cameras, there can be food relief. No cameras, no aid. In light of this, how could the World Food Programme build its computer game Food Force without even one single PR tier?

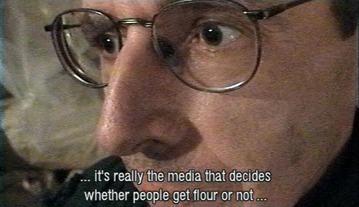

video still from Episode 1, © Renzo Martens

Episode 1 takes us through many such media-laden scenarios. In an open market destroyed no more than thirty minutes ago by Russian Federation soldiers with tanks and heavy artillery, a woman recounts how she and the other market women formed a human shield to halt the execution of a group of Chechen boys. Speaking to the camera, in an oddly well-rehearsed role of who stands where and who says what to the camera, the woman is still shaking from the experience. The scene ends with Martens staring shamefaced at the ground, unable to gather enough gumption to ask her what she thinks of him.

At a food distribution centre, Martens addresses a group of women lined up to receive rations of oil and flour. ‘I just want to ask you what you think of me!’ and this time there is an answer. The grim situation of lining up to receive basic foodstuffs, fades in the face of humanising laughter and warm sparkling eyes, women just being women. For a moment the food queue has all but disappeared. ‘Boy, I think you’re handsome, with your blue eyes!’ ‘What’s your theme?’ ‘Are you a journalist?’ ‘No, he’s an artist.’ ‘I think he’s a journalist.’

video stills from Episode 1, © Renzo Martens

Ultimately Martens ‘act’ of showing up with his camera and popping the question brings humanity to every situation that he creates. When he meets a young woman in a refugee camp (who bears an uncanny resemblance to his true love back in Belgium), his question changes, ‘How should a man let a woman know that he loves her?’ the woman’s answer, delivered with beaming smile and sparkling eyes, dissolves the miserable tent landscape and suddenly it’s just two people (and their translators) talking about love and life.

Of course Martens created this film for an art context, and the film articulately addresses contemporary art issues. Quite possibly Martens would be appalled that I consider his film to be ‘useful’, not just for artists and an art public, but as a tool to talk about the causes of war, hunger and the politics of emergency food distribution. And the question that Martens dares to ask amidst flying bullets, UN press conferences, annoyed Russian soldiers, women in food queues and refugees living in tent camps, the initial struggle that it initiates in the interviewee and in me, the audience, as I am simultaneously embarrassed by this question, but know that it is a question that can air-lift all of us actors out of the immediate and into a larger, more important discussion. Complexity is not complicated. Episode 1 brings us to the next tier, where a complex situation can be discussed with the nuance it deserves.

video still from Episode 1, © Renzo Martens

technorati tags: food-related film, Episode 1, Renzo Martens, Chechnya, cinema, emergency food distribution, Food Force

debra at 11:17 | Comments (4) | post to del.icio.us

Food Force computer game: force-feeding inaccurate notions of the causes of hunger

March 17, 2006

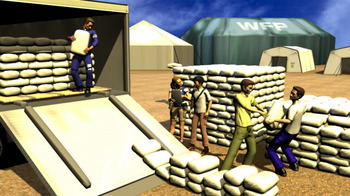

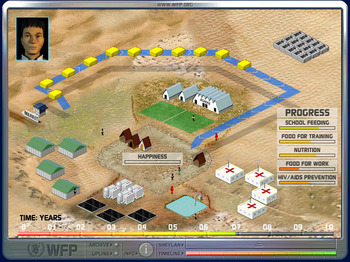

images courtesy of Food Force, © United Nations World Food Programme - all rights reserved

Two weeks ago I sat dumbfounded watching a French TV report in which journalism students practiced reporting a fictional national emergency. I couldn’t help but think that what’s cool about practice is that it makes perfect. If you practice having enough crises, you might actually get really good at having one! This hackle-raising report about teaching young adults to respond positively to crisis, just didn’t seem to me like a simple exercise on getting prepared. The TV experience was absolutely colouring my thinking when I came across the UN’s World Food Programme (WFP) website and discovered a new computer game for school kids called ‘Food Force’.

‘A major crisis has developed in the Indian Ocean, on the island of Sheylan. We’re sending in a new team to step up the World Food Programme’s presence there and help feed millions of hungry people.’

That’s pronounced ’shay-lawn’ by the way. The Food Force computer game is essentially a communications campaign of the UN’s WFP, cleverly disguised as an educational tool. Although the game really does teach kids about mid-crisis food distribution, its purported goal, teaching students about the causes of hunger, is framed exclusively in the short term and completely ignores all of the long term causes.

images courtesy of Food Force, © United Nations World Food Programme - all rights reserved

Food Force has six game tiers reflecting the basic elements of emergency food distribution: air surveillance (helicopter reconnaissance, counting clumps of roving refugees), energy packs (achieving nutritional and economic balance from rice, beans, vegetable oil, sugar and iodized salt), food drop (aim and drop those rations), locate and dispatch (Tetris-like global food collection), the food run (choosing the right route through hostile territory), and future farming (dealing with a combination of long term hunger solving factors).

Predictably my favourite game tier was ‘future farming’, where I was taught that paying people in food to attend job training programmes and so investing in the community, was the straightest path to community self-sufficiency and societal well-being. Together with the food pack nutritional assembly tier, this was the game tier with the highest educational value, going beyond point and drop and mouse dragging I mean racing.

images courtesy of Food Force, © United Nations World Food Programme - all rights reserved

Food Force has a website chock-full with extra video, images and an educational package enabling teachers to work this computer game seamlessly into the curriculum. I pored over the WFP site in search of information addressing what I believe to be the long term causes of hunger and the long-term perspectives on solving the problems. Alas, I could find none. According to Food Force, hunger is caused by drought and civil war.

Of course I find no fault with the WFP’s symptomatic relief efforts per se, nor do I see intentional evil with a communication strategy that illustrates this practice to children in the form of a computer game. But I do have a problem with placing this game in a curriculum that teaches children that the cause of hunger is simply drought and war. What are the some of the causes of drought? What are the some of the causes of war? What causes such a lack of food security that climactic fluctuations can take out several million people? Food Force offers no macro vision, and I do find fault with weaning children of the notion that food security is rested in global food politics. The macro vision of many commonly accepted causes of hunger, such as the small farm community-destroying effects of large-scale agricultural practice and the methods of monoculture, are left completely unaddressed by the WFP’s computer game.

images courtesy of Food Force, © United Nations World Food Programme - all rights reserved

I often wonder if teaching children about hunger couldn’t happen in a more nuanced way. Wouldn’t it be more productive than training them to throw a little money at the problem? Well, maybe not with the ‘throwing a little money at it’ method of famine-control being so lucrative.

Tomorrow, I’ll give an example of a solution.

I promise.

technorati tags: World Food Programme, Food Force, computer game, emergency food distribution

debra at 18:26 | Comments (2) | post to del.icio.us

When good salami happens to bad people

March 13, 2006

You know how you sometimes get a song in your brain that has absolutely no reason being there?

‘Jesus is just all right, Oh yeah.’

Well, I’m just glad I wasn’t responsible for naming this Languedocian kilo of pork product as big as your head.

Dang the Salaison de Chateauneuf de Randon! In a time of (staging) the torching of embassies, this seems to me a rather subversive name for a salami.

Do, do, do, do, do, do, do.

Do, do, do, do, do, do, do.

Do, do, do, do, do, do, do.

Do, do, do, do, do, do, do.

On the bright side, the Netherlands has shrugged off the shackles of right-wing popular support. Lordee!

debra at 14:38 | Comments (2) | post to del.icio.us