An improbable history: meal assembly centers

March 26, 2006

image of friendly community hugging © Super Suppers, used entirely without permission

Kim Severson and Julia Moskin’s New York Times article about meal assembly centers has me all excited and flapping my wings. For other people. They report on Texan Judie Byrd’s service called Super Suppers, based upon the concept of the communal kitchen.

Here’s how it works: a suburban working person with family goes sans entourage to a central food preparation center where the food is prepped and waiting in a professionally stocked and staffed kitchen. Meandering from station to station (s)he assembles the week’s family meals, takes them home in zip-lock baggies made from compostable potato starch, freezes the meal-sized portions and heats them up when it’s time to get the grits on the table.

What is not to like about this practically utopian idea, for other people? As a predominately self-employed happily not married person with zero children, and as someone who finds almost all elements of food preparation thrilling, I realise this business model was not made with people like me in mind. But because I am insane and live in a bubble, here’s what I’m imagining:

1. The meal assembly center would stock its food exclusively from local farmers and artisanal producers, procuring the highest quality seasonal and local produce at a fair price. The meal assembly center would develop enduring relationships with these folks and the community using the meal assembly center would feel secure knowing that all of the food products they are using are made or grown with their well-being in mind.

2. In a professional kitchen with sharp knives and a seemingly limitless amount of freshly ironed tea towels (made from locally grown hemp), the meal assembly center’s assisting chefs have prepared cooking stations for an interesting range of recipes. This week there are cuts of meat from the local deer cull and some strange root vegetables, next week it’s traditional holiday fare from one of the region’s thirty-seven ethnic groups, the week after that, it’s all about vegan haute cuisine.

Whale washed up on the beach? No problem. The meal assembly center is hip to the community and the kelp is already rinsed. Finally you’re cooking as if you live where you live!

3. It used to be common to take homemade bread dough to a communal bakery for baking. Heq, it used to be common for a lot of people to be involved in the family’s cooking, sharing the workload, but also sharing the how-to and the chit-chat. At the meal assembly center, labour intensive dishes involving lots of stuffing, rolling, stretching and braiding could be prepared by the organisation or by other folks sharing the kitchen with an interest in these dishes. It would be a community that cooks, just like it was way back when, in the Wabac Machine.

image of Peabody and Sherman using the WABAC Machine (that’s pronounced ‘way-back’) © Jay Ward, used entirely without permission

4. The meal assembly center would be stocked with amazing community-tested equipment. Here’s your chance to try cooking on a wood burning stove. Want to smoke up some trout, stuff some sausage, make cheese, brew a stout beer? It’s all possible because the community would do it together.

If you have prepared food (for your family) in a food preparation center, I would really love to hear about your experience. But please do not burst my bubble and tell me it’s about Thai Mac ‘n Cheese and Turkamales.

image of zip-lock wielding working yoga mom © Super Suppers, used entirely without permission

- Kim Severson and Julia Moskin’s New York Times article on Super Suppers,food preparation centers

- Super Suppers

- Judie Byrd’s website

- Sara Wilson at Entrepreneur dot com talks about the business concept of Super Suppers

- Peabody’s Improbable History

- A blogger (let’s call him Greg from Life’s a Picnic) writes about his Super Suppers experience.

- Dream Dinners, just another meal assembly center

- Dr. Gurgles doesn’t feel at ease with the concept

- Even more Gurgles from a time long past. Respect to the Gurgling Cod has followed this story in all its New York Times Magazine ugliness from the start.

technorati tags: food preparation centers, meal assembly centers, working moms, locative food, food trend, coommunity

debra at 22:40 | Comments (15) | post to del.icio.us

Not cooking with flowers and leaves, a raw food recipe for marinated shitake mushrooms

March 21, 2006

If I want to eat with my friends, I can’t just serve up vegetables with the dirt still clinging to the rootball, the way I like it. I have to engage in some refining.

Hibiscus flower and green tea leaf marinated shitake mushrooms

(work: 7 minutes, wait: 1-4 hours)

- dried hibiscus flowers

- whole green tea leaves

- water

- fleur de sel

- lemon zest

- crayfish oil (vegetarians, relax)

- two shitake mushrooms

In the bottom of a cup, pour enough hot water to cover a layer of hibiscus flower and green tea leaves. You’re going to make a highly aromatic and concentrated tea, something too strong to sip. Aim at producing four tablespoons.

(This year, hibisicus flowers seem to be my souring agent of choice. I find it hypnotising to watch the magenta colour leach out of the petals, and I just live for the ‘powdery’ aftertaste.)

Add to the ‘tea’ a big fluffy pinch of finely zested lemon peel, a goodly amount of fleur de sel, and a teaspoon or two of *crayfish oil.

Adjust the marinade and toss around with two large shitake mushrooms. Marinate for one to four hours before serving. Everytime you walk by, just toss the mushrooms lightly for fun.

You can keep the mushrooms for about a day without ruining the texture in or outside of the fridge. The marinade and juices leached out of the mushroom can be ‘recycled’, it’s like bouillion for raw foodies. You know how I love the food recycling!

*A note on crayfish oil: you can’t buy it. Mine was a cadeau made by my friend Marlein, to whom this recipe is dedicated. Possible (vegetarian) substitute: grape seed oil, barely warmed and barely covering half a fennel, star anise and a dried hibiscus petal. Leave to cool and sit for two days. Remove the ’stuff’ and decant to a very clean jar. Store in a cool, dark and dry place.

*A note about using non-vegetarian, non-raw ingredients in this recipe: relax and enjoy delicious foods that have been made for you with love. Aromatic oils are like parfum, you need only a few drops. In this recipe you will need enough drops to fill a teaspoon or two.

Both the green tea leaves and the crayfish oil have a powdery ‘note’ that compliments the woodiness of the shitake. This marinade smells like peonies. Shitake pivoine! My hands are parfumed from the shitake tossing.

The recipe is dedicated to my dear friend Marlein Overakker, a chef who has turned me on to my favourite parfums and who is always a huge source of inspiration.

technorati tags: raw food recipes, vegetarian, shitake, mushrooms, cooking with flowers, cooking with tea, green tea

debra at 14:14 | Comments (9) | post to del.icio.us

Episode 1, emergency food distribution and the role of the cameras

March 19, 2006

- This entry refers to food distribution as discussed in yesterday’s entry about the World Food Programme’s computer game, Food Force.

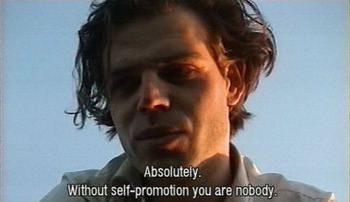

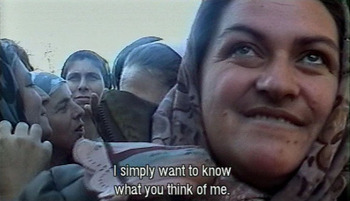

video still from Episode 1, © Renzo Martens

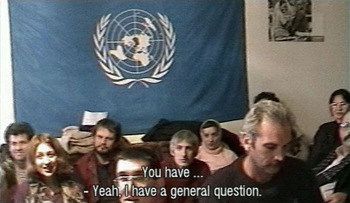

In January 2004, Dutch artist Renzo Martens produced his forty-four minute art film, Episode 1, a documentation of an extensive art performance. Martens travelled to the hottest hot spot war that he could find at the time of making the film (Chechnya, 2002), and in this ’setting’ he pointed the camera, not at the war’s victims and/or perpetrators like most (news) cameras do, but back upon himself. In Episode 1, Martens asks his Chechen and Russian Federation subjects, ‘What do you think about me?’

Enough about you, let’s talk about what you think about me.

Martens subjects are the normal cast of characters in every war; heavily armed soldiers on border patrol, civilians lining up for food, civilians trying to get on with it, civilians suffering before their destroyed homes and lives, refugees, but also all manner of NGO employees with their food programmes and journalists with their stories. Within minutes we understand that this is not simply a film about war, but a film about the role of the camera in war, about ethics, the dehumanising effect of pointing the camera and about what is so humanising about turning the camera back around at one’s self.

video stills from Episode 1, © Renzo Martens

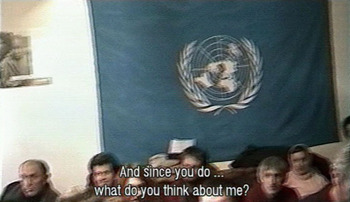

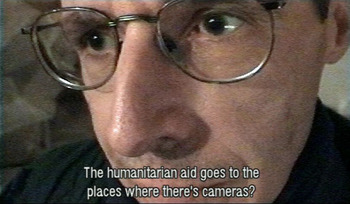

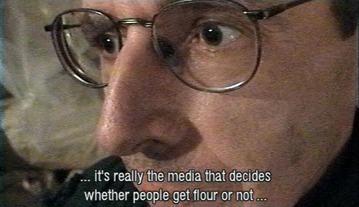

In the tense environment of a Chechen UN press conference, in territories under fire, the conference moderator asks a group of journalists, NGO employees and UN workers, ‘Does anyone have any questions?’ Martens pipes up, ‘Yes, I have a question!’ ‘What do you think about me?’ Peals of laughter, no one can believe their ears. Ultimatey Martens’ question is ignored and the journalists and NGO employees disband to their SUV convoys, rushing off to yet another ‘opening’ of a milk powder storage facility. Martens interviews the director of the operation, and together they quickly establish the fact that where there are cameras, there can be food relief. No cameras, no aid. In light of this, how could the World Food Programme build its computer game Food Force without even one single PR tier?

video still from Episode 1, © Renzo Martens

Episode 1 takes us through many such media-laden scenarios. In an open market destroyed no more than thirty minutes ago by Russian Federation soldiers with tanks and heavy artillery, a woman recounts how she and the other market women formed a human shield to halt the execution of a group of Chechen boys. Speaking to the camera, in an oddly well-rehearsed role of who stands where and who says what to the camera, the woman is still shaking from the experience. The scene ends with Martens staring shamefaced at the ground, unable to gather enough gumption to ask her what she thinks of him.

At a food distribution centre, Martens addresses a group of women lined up to receive rations of oil and flour. ‘I just want to ask you what you think of me!’ and this time there is an answer. The grim situation of lining up to receive basic foodstuffs, fades in the face of humanising laughter and warm sparkling eyes, women just being women. For a moment the food queue has all but disappeared. ‘Boy, I think you’re handsome, with your blue eyes!’ ‘What’s your theme?’ ‘Are you a journalist?’ ‘No, he’s an artist.’ ‘I think he’s a journalist.’

video stills from Episode 1, © Renzo Martens

Ultimately Martens ‘act’ of showing up with his camera and popping the question brings humanity to every situation that he creates. When he meets a young woman in a refugee camp (who bears an uncanny resemblance to his true love back in Belgium), his question changes, ‘How should a man let a woman know that he loves her?’ the woman’s answer, delivered with beaming smile and sparkling eyes, dissolves the miserable tent landscape and suddenly it’s just two people (and their translators) talking about love and life.

Of course Martens created this film for an art context, and the film articulately addresses contemporary art issues. Quite possibly Martens would be appalled that I consider his film to be ‘useful’, not just for artists and an art public, but as a tool to talk about the causes of war, hunger and the politics of emergency food distribution. And the question that Martens dares to ask amidst flying bullets, UN press conferences, annoyed Russian soldiers, women in food queues and refugees living in tent camps, the initial struggle that it initiates in the interviewee and in me, the audience, as I am simultaneously embarrassed by this question, but know that it is a question that can air-lift all of us actors out of the immediate and into a larger, more important discussion. Complexity is not complicated. Episode 1 brings us to the next tier, where a complex situation can be discussed with the nuance it deserves.

video still from Episode 1, © Renzo Martens

technorati tags: food-related film, Episode 1, Renzo Martens, Chechnya, cinema, emergency food distribution, Food Force

debra at 11:17 | Comments (4) | post to del.icio.us